March 20 Evanston, Wyoming to Cheyenne, Wyoming

Interstate 80 guides us through the bulk of southern Wyoming where snow blankets the mountains but not the freeway, to our relief. We may have hit this region at its prettiest time of year. Built-in barricades dot the interstate, ready to block access at a moment’s notice, as happened during last week’s blizzard. Other freeway exits along this stretch bear names like “Sand Creek Massacre Trail.”

“Nothing good happened there,” Jim says.

My brother James loves history as much as we do and lived in Wyoming for several years, so he had some sightseer recommendations for us, including the Rawlins Frontier Prison Museum. Unfortunately we missed their tour hours but the exterior alone surely offered a great deterrent to a life of crime for anyone in the wild west, or now.

Every person we’ve encountered in Wyoming has treated us with unfailing kindness, like we accidentally stumbled into Canada. At the C K Chuck Wagon restaurant in Laramie, we befriended our 20-something waitress who told us of her planned road trip to Oregon next week, camping along the way. She had a question about Portland, she said, and I prepared to answer about riot locations. Instead she had a dream to dine at a restaurant overlooking the city’s river. Did we have any suggestions?

Jim and I were stumped. It dawned on us that river-view dining’s not such a huge thing back home. The ocean, yes. But not so much in Portland or Salem.

I have no idea why, nor do I know why it’s never occurred to me why we care so little about watching water flow while we eat in Oregon. Maybe because we so often have to watch it fall while we eat? Or maybe Jim and I just don’t get out enough to notice such phenomenon, especially in Covid, especially in Portland. Travel offers all manner of insight. Anyway, we later thought of some river-options, but still stand by our recommendation that our young waitress and friend hunt down a McMenamins instead.

In Cheyenne we attempted to locate my parents’ first real home in a modest basement apartment in the city center. Shortly after his dental school graduation in 1956, Captain Tyler reported to Warren Air Force Base in Wyoming’s capital. Sadly, their house has since disappeared. Still, we got a flavor of the area and called Mom up to describe what we saw. We walked the neighborhood while Mom strolled down her own newlywed memory lane with us over her landline. (Postscript: Turns out that Mom gave us the wrong address. The little white house yet stands.)

March 21 Cheyenne, Wyoming to North Platte, Nebraska

Last night an apparent gang of gymnasts booked the room overhead and practiced their moves until 10:15 PM (Jim clocked it.) Of course it almost certainly was a young family with kids either ADHD or simply bursting with energy on a road trip. “Either that, or a group of raccoons jumped off the bed all evening,” Jim suggests.

We managed a good rest, nonetheless, and are off on our shortest drive of our trip, the happy result of that schedule jumbling we had to do to circumvent snowstorms.

Before coming to North Platte, Nebraska, all we collectively knew about Buffalo Bill Cody was Jim recalling that Bill had a sidekick in Annie Oakley. We had so much to learn. Buffalo Bill worked as a Pony Express rider, Union Army scout, buffalo hunter, and showman before building his retreat ranch in North Platte.

Nebraska eventually acquired Bill’s house and land, turning it into a state historical park and living history museum. Unfortunately, the house hadn’t opened for the season yet, but we could wander the grounds and peer into Bill’s mansion. I appreciated the explanatory signs placed on the outside of the windows for gawkers like me. One note on the back door had the standard Covid list listing virus symptoms like high fever or difficulty breathing, and if visitors suffered any of them, to “please reconsider”entering.

You might not know a world-wild pandemic existed if you only visited parts of Nebraska. Not just guests, but waitresses and store clerks apparently never got the memo. We just remind ourselves we’re vaccinated.

The folks at the Golden Spike Tower, however, seemed to have heard about the coronavirus and we got to observe the world’s largest railroad yard from their lookout above. Studying a map of the United States, it makes sense why Union Pacific centered their transportation hub here.

We know a ton about the Oregon Trail, but Oregonians rarely learn much about the history of railroads in the United States. Perhaps that’s because our pioneers with their schooner wagons beat the rail lines out to the west coast, with other supplies arriving directly by ship via the Pacific Ocean. But now we better understand the significance of the railroad in the early development of our country as a whole.

What most caught our imagination at the Golden Spike, though, was the story of the North Platte Canteen. Throughout World War II, six million troops passed through town while traveling to their assigned training base or battlefront. The good people of the North Platte area made it their mission to greet each train no matter what time of day or night with no advanced notice due to wartime secrecy.

For decades, soldiers looked back fondly on their short stops in North Platte for a cookie or candy bar, newspaper, cup of coffee, and especially a kind word with the pretty young gals waiting there. These servicemen said the women reminded them why they were going to war in the first place. Some of these women also volunteered to serve as pen pals, placing their names and addresses inside popcorn balls for a soldier to take along with them. A number of these connections eventually resulted in marriage.

Whenever Jim and I hike through the old army training grounds of Camp Adair near Salem, I think of the young soldiers who got dropped off at the railroad station there on their first steps towards war. Many of these servicemen had probably stopped for 10-15 minutes at the North Platte Canteen. I picture these young soldiers enjoying a snack and a chat with the caring women of Nebraska as they journeyed further out west, their spirits lifted, if just for a bit.

March 22 North Platte, Nebraska to Saint Joseph, Missouri

Today we drove through Willa Cather country and I thought of her classic 1918 novel about the Nebraska plains, My Ántonia.

Jim observed, “Nebraska is impressively flat.”

We had some challenges with persistent rain and mud and the dog fantasizing that maybe if she balked when it was time to enter the car, we’d change our minds about this whole cross-country driving idea.

Lots of other people have migrated through these parts--just the other direction--including Lewis and Clark and Oregon Trail pioneers. Our friend Maureen suggested a stop at Fort Kearny, possibly named for her ancestor, known as the kick-off spot for pioneers traveling west. I visualized my Oregon ancestors assembling their supplies here as they prepared for their journey to the Willamette Valley.

As a state-run park, Fort Kearny strictly adhered to Covid rules, shuttering their museum and layering their books with sheets of plastic. But the eager volunteer at the desk still wanted to help as much as she possibly could.

“I can pull a book out for you, if you’d like. Otherwise all we have are these kids’ toys for sale,” she said, holding up a laminated sheet of colorful stuffed animals depicting something Nebraskan.

I thanked her and she answered, “You betcha,” which made the entire stop worthwhile, as far as I’m concerned.

The people of Nebraska and Missouri have been unusually friendly--men holding doors open for me, offering water for Sophie. Not only does chivalry still exist here, cigarette smoking apparently does, too. Our room here in Missouri reeked of nicotine but I was planning to overlook it until I saw the placards on the desk warning of $250 fees for smoking in the room. We got a quick room change. Later I saw the name of the attached hotel restaurant: “Badass BBQ: Smell That Smoke.”

My research on Saint Joseph, Missouri uncovered an impressive row of 100-year old-gilded homes in various states of repair called “Hall Street Historic District,” supposedly an architect student’s delight. I’d regretted we couldn’t stay at one of these restored mansions, now a Bed and Breakfast, because of the dog. Instead we are lodging at a Drury Inn off Interstate 29, a SWAT team greeting us on the other side of the freeway upon arrival.

We drove downtown to explore the mansion row and Jim started sweating. The B & B was one of the few restored houses; most remained in serious decay, and the neighborhood felt downright scary. We dared not leave the relative safety of the Honda, Jim grateful to have our own guard-dog monitoring the situation from the backseat.

“Where are all the cars? Where are all the people?” Jim cried. The area, like much of what we witnessed of Saint Joseph, appeared derelict and nearly abandoned at 5 PM on a Monday. We had hoped to see Jesse James’s house museum but didn’t mourn its closure: Jim wanted to haul back to the relative sanctuary of our hotel, ASAP.

Back at the Drury Inn, Jim researched Saint Joseph on the internet. Turns out it suffers the second highest rate of violent and property crime per capita in the United States.

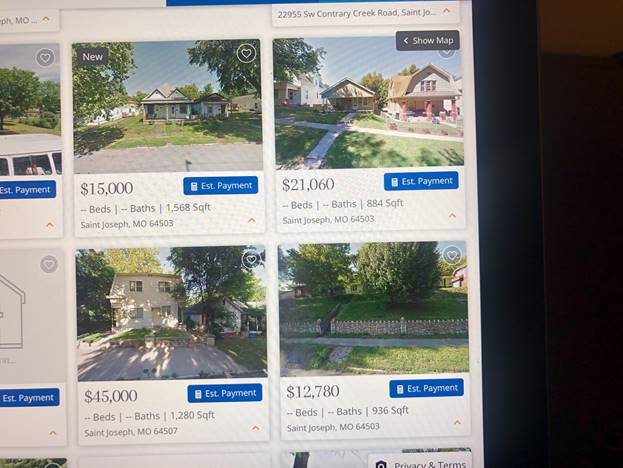

You can score a fixer-upper for $11,000 or a decent-looking house for $24,000 here. A fully restored mansion is yours for only $422,900.

The SWAT team has departed, and we now hear only the occasional wail of police sirens.